Resembling a huge, ripe, cracked brie, one of the few remnants of the Nazis’ attempts to make Berlin a world capital of the Thousand Year Reich they claimed would be “comparable only to ancient Egypt, Babylon or Rome” now sits surrounded by shabby, peach-coloured residential blocks in the south of the city.

The monstrous concrete cylinder, with a 21-metre radius and weighing the equivalent of 22 Airbus A380s, juts out of the ground more than four storeys high and descends a further 18 metres under the surface. It is a chilling symbol of what might have been, had the Nazis managed to realise their plans.

The so-called Schwerbelastungskörper, or “heavy load test structure”, was built to simulate the weight of one of the four pillars of the 120-metre high Triumphal Arch, planned for the north-south axis of Germania, and marks the spot where the north-east pillar would have stood.

“Berlin’s swampy ground was seen as a potential hindrance for such a massive structure, so the engineers of the German Society for Soil Mechanics were commissioned to check the extent to which it would have to be reinforced,” says Micha Richter, a Berlin architect and leading member of Berlin Underworlds, an association that holds tours of historic sites across – and mainly underneath – the city. “Its 12,650 tonnes of concrete were poured over seven months in 1941,” he says. French PoWs were among those deployed in its construction.

The Berlin historian Gerlot Schaulinski, who curated the exhibition Mythos Germania, argues that the concrete cylinder emphasises the huge mistake in the common perception of Germania as an architectural chimera, detached from the hateful regime which conceived it. Rather, a closer look at the inhumane and murderous methods used to achieve it leaves Germania as a concise reminder of what Nazism really was.

The relationship between the building craze sparked by Germania and the concentration camps could hardly be closer. The demand for labour and materials led to many of the camps being built very near to quarries – among them Gross-Rosen, Buchenwald and Mauthausen, now all bywords for human suffering. Sachsenhausen was nearby to a planned brickworks. Germania was all too real for the tens of thousands who died in the task of quarrying stone or baking bricks for it, not to mention the many PoWs who made up a 130,000-strong workforce in Berlin. Demand for labour was so great that from June 1938, police forces were ordered to round up any male beggars, tramps, Gypsies or pimps fit to work. Many of the forces were so delighted at the opportunity that they provided far more “misfits” than had been required, including hundreds of the city’s homosexuals.

Many thousands of ordinary Berliners also felt the sting from 1939, as they were forcibly rehoused to make way for the new city, the government buying up much of the property that was to be destroyed. Often they were given new homes where Jewish families had lived, as the Jewish citizens were moved to ever more cramped accommodation, and later to ghettos and then concentration camps. So it was that Germania had a crucial role to play in enabling Nazi authorities to carry out the Holocaust, its plans leading to Jews being driven from their homes even before the pogroms of November 1938.

Had they succeeded, the capital of the Third Reich, in keeping with the wishes of Adolf Hitler and his general building inspector, Albert Speer, would have been altered beyond recognition. Broad swathes of the city would have been swept away – including between 50,000 and 100,000 houses – and old structures like the Reichstag and the Brandenburg Gate, which seem plenty large enough to the modern eye today, would have been swamped by new building compositions of massive proportions.

The designation Welthauptstadt Germania, or World Capital Germania, often believed to be the official name given by the Nazis, is – like many of the project’s details – in fact a historical misnomer.

“The name only emerged after the publication of Speer’s 1969 memoirs, Inside the Third Reich, and is actually based on casual remarks made, we believe, just twice by Hitler in conversation with a close circle of acquaintances,” says Schaulinski. “It combines the image of a visionary city of the future with that of a megalomaniac dictator. Now, ‘Germania’ stands for the hubris of the Nazi system and the failure of those big plans, because it only exists in drawings and model images.”

Schauinski points out Speer’s use of the name served him well during his postwar portrayal of his role in the project. “It supported his attempts to prove the strength of Hitler’s allure and why Speer – the architect, the artist – was so taken in by his egotism. It serves to divert our attention from architectural castles in the air and therefore manages to purposely blank out the criminal consequences of the project.”

Among the historical truths we now know about Germania, some of which have only come to light in recent years, is how Speer drove Berlin Jews from their homes, as well as his active support of deportations of Jews and others to concentration camps, and how, in cooperation with the SS, he ensured the Nazi’s slave labourers produced the building materials he required. His plans seemed so extraordinarily ambitious that even his own father told him he was crazy.

“Amid the aspirations to tear down and rebuild large parts of the capital, visions and crimes were inextricably linked,” says Schaulinski.

‘A nightmarish city’

There is evidence to suggest Hitler had started mapping out his plans as early as 1926. The two postcard-sized sketches he made then of the Great Arch, which he envisaged as a reinterpretation of Germany’s defeat in the first world war and was to have been engraved with the names of Germany’s 1.8 million war dead, he handed to Speer in the summer of 1936.

The following year, on the fourth anniversary of his rise to power, he created the Inspector General of Buildings (GBI), appointing Speer its head. The GBI was tasked with planning and organising the comprehensive redevelopment of Berlin that was to correspond with Hitler’s conquest of Europe.

The plans centred around a grand, seven-kilometre (4.3-mile) north-south avenue, which was to link two new railway stations. The crowning jewel was to be the Great Hall, inspired by the Pantheon, whose dome would have been 16 times higher than that of St Peter’s in Rome. As the largest covered space in the world, designed to take 180,000, its planners harboured concerns over the effect the exhaled breath of so many might have on the atmosphere inside.

Connecting the Grand Hall and the Great Arch along the new axis were to be a vast array of new buildings for business and civic use, flanked by wide avenues (broad enough to fit large numbers of marching troops), a vast artificial lake and a large circus of ornamental Nazi statues. Plans also included a complex new system of roads, ring roads, tunnels and autobahns.

While the scale is still hard to imagine, what is clear is that Berlin would have been transformed from being an attractive living space for its citizens into a daunting, theatrical expanse, the main purpose of which would have been to allow the state to show itself off. The scale would even have reduced Hitler to an insignificant pin prick when he addressed crowds from the Great Hall – a point that concerned some of his advisers. Architects and urban planners who have analysed the city in recent years claim it would probably have been nightmarish to live in: hostile to pedestrians, who would regularly have be sent underground to cross streets, and with a chaotic road system, as Speer’s did not believe in traffic lights or trams. Citizens would have been made to feel variously impressed and inhibited by the towering structures around them.

Schaulinski points to a 2013 sculpture by the Colombian artist Edgar Guzmanruiz, also on display at Mythos Germania (a permanent exhibition opened in a shaft of the Berlin underground station), as giving one of the best impressions as to how the city would have looked. Guzmanruiz has superimposed a transparent Plexiglas mold of Germania over modern-day Berlin.

Schaulinski jokes that the current-day cuboid chancellery building, nicknamed the “washing machine”, which many criticised for being wildly oversized when it was completed in 2001, “looks like a garage” next to the Führerpalast, and the Reichstag building – seat of the German parliament – “like an outhouse”.

Anyone wanting a hint of the scale aimed at can visit Berlin’s Olympic Stadium, Tempelhof airport or the former Reich Air Transport Ministry (now the finance ministry) for examples of Nazi architecture. But remnants of authentic Germania are not easily found today. There is the avenue running westwards from the Brandenburg Gate, the east-west axis now called Strasse des 17. Juni, which is still flanked by Speer-designed, and – it cannot be denied – rather graceful doubled-headed street lamps.

There is also the Siegesäule, or Victory Column, on the other end of the avenue at the Grosser Stern, which was moved from the square in front of the Reichstag to make way for a parade ground on the planned north-south axis. Originally unveiled in 1873 to mark numerous Prussian victories, the Victory Column was lengthened, on Hitler’s insistence, by the insertion of an additional drum into the pillar. In the southern city of Stuttgart there are traces of Germania: the 14 travertine columns fashioned out of “Stuttgart marble” for the planned Mussolini Platz in Berlin – but never delivered after the outbreak of war impeded their transport – today form the property border of a huge waste-incineration plant.

But it’s the test load concrete plug, which many would like to have been destroyed at the end of the war had its sheer size not made that virtually impossible, that is arguably the clearest reminder. It continued to be used as an engineering test site until 1984, before efforts were made in recent years to turn it into everything from a climbing wall with a cafe on top to a car showroom. But campaigners fought to have it preserved as a silent reminder of what might have been, and it now attracts thousands of visitors on guided tours every year. “It shows better than anything how it was a project where no compromises were to be made,” says Richter.

Banking on conquest

Buffeted by a fittingly chilly April wind, Richter walked me up to a 14 metre-high viewing platform next to the concrete form for a soaring view across the city, with scores of cranes indicating the huge amount of postwar reconstruction that is still going on across Berlin. “This is the best impression you really get of just how crazy the Germania project was,” Richter explains. “On the plans it all looks fairly flat, but here you see the extent to which they planned to completely change the topography of the city.”

The ground level of the Triumphal Arch site was to have been raised by 14 metres, “creating an optical illusion allowing a stage-managed view of the Great Hall, the prime object on the north-south axis, within the arch,” Richter says. The test structure would have been buried underneath the elevation and sealed by the arch, which would have stood three times as large as Paris’s Arc de Triomphe. It was just one small section of the mind-boggling plans to transform the city into a gargantuan and imposing metropolis.

But just because only a few traces and plans survive, it is a mistake to see Germania as something that only existed in theory, and which was unrealisable, insists Wolfgang Schäche, an architectural historian and expert on the topic.

Workers reshaping Berlin’s Tiergarten district in around 1938.

“It was never a utopia, rather a very concrete, ideologically loaded projection of architecture and urban construction. All the ideas were checked by engineers and the best constructors of the time, and the Germania project had the support of an entire elite of German building experts who were actively involved in it, so that there is next to nothing – even the Great Hall – which would not have been technically feasible,” he says.

The plans to demolish large swathes of the capital were in fact only helped by the massive allied air strikes on the city, as Speer himself liked to point out. One of the senior members of his planning department, Rudolf Wolters, went so far as to write in his diary after one particular attack: “Today once again the destruction by the allied bombers has assisted us greatly in our planning efforts!”

While it was impossible not to know of the restructuring plans, most details of the project were kept secret from ordinary people. Even the architects commissioned to build individual constructions were often not made aware of the other buildings that would be in the vicinity. No press reporting on the scheme was allowed without it going through the censors of Speer’s GBI.

For a while a trio of political satirists called Die Drei Rulands managed to poke fun at the town planners on the very public stage of a leading cabaret venue. In one musical number that addressed the plans to change the course of the River Spree to accommodate the Great Hall, they sang: “Yes, through Berlin it still flows, the Spree / But from tomorrow it’ll go through the Charité”, a reference to the city’s largest hospital. Unsurprisingly, in January 1939, they were slapped down with a lifetime performing ban by propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels.

Somewhat ironically it was the war that got in the way of Germania not being realised, as resources and attention – including Speer’s, following his appointment by Hitler as his minister of armaments and war production – was diverted elsewhere. The plans were to have been resumed at full throttle following a German victory, when the nations over whom Hitler expected to conquer would provide an endless supply of labour and materials. “Which is precisely why there was never any discussion about what the whole scheme was supposed to cost,” according to Schäche. “Right from the start, Speer was banking on materials and financial means that would be stolen from people now subservient to Germany.”

The extent to which money was never seen as an obstacle to realising Germania is illustrated by an anecdote about a visit made by Speer and his planning department to Horcher, one of the most popular VIP restaurants of the day, in which the group was seen slapping their thighs after one of them remarked: “Normally an authority has to shape its spending according to its income. We’re able to do precisely the opposite!”

Today, while Germania seems like a distant nightmare it still maintains a certain hold on the city. The government district of the “new Berlin”, following the 1991 move of the capital from Bonn, was deliberately built on the opposite axis to the one planned by Speer, a move that its architects described as “historical decontamination”.

From the viewing platform above the heavy load test structure, Richter points out an area in the district of Tempelhof-Schöneberg that has recently been the focus of strife between the government and renters. From 1938, around 1,000 properties worth a total of 200m Reichsmark were bought up by the authorities, for a price fixed by them, to enable the building of Germania. “They were marked ‘for destruction’ to make way for the so-called Great Road between the Triumphal Arch and the Great Hall. The residents were given similar properties elsewhere in the city and Jewish residents were moved in temporarily before theywere deported to concentration camps.”

Property prices in Berlin are currently booming. So it’s hardly a surprise that the present-day federal government, who still owns those properties (they never were destroyed) and knew it was sitting on a gold mine, announced that they would sell them off to the highest bidder. The reaction from the local residents fearful of being pushed out of their homes by increased rents set by private investors was bitter and angry.

“So you see how the traces of Germania are still to be found even now,” says Richter, digging his hands into the pockets of his thick winter coat.

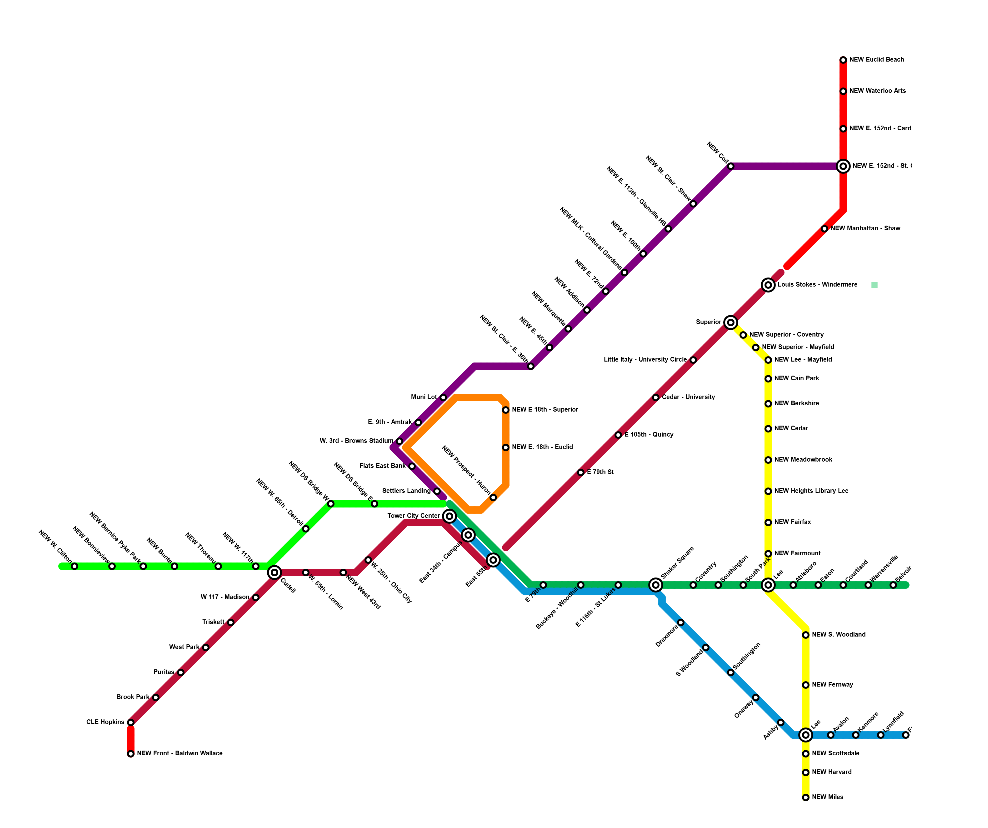

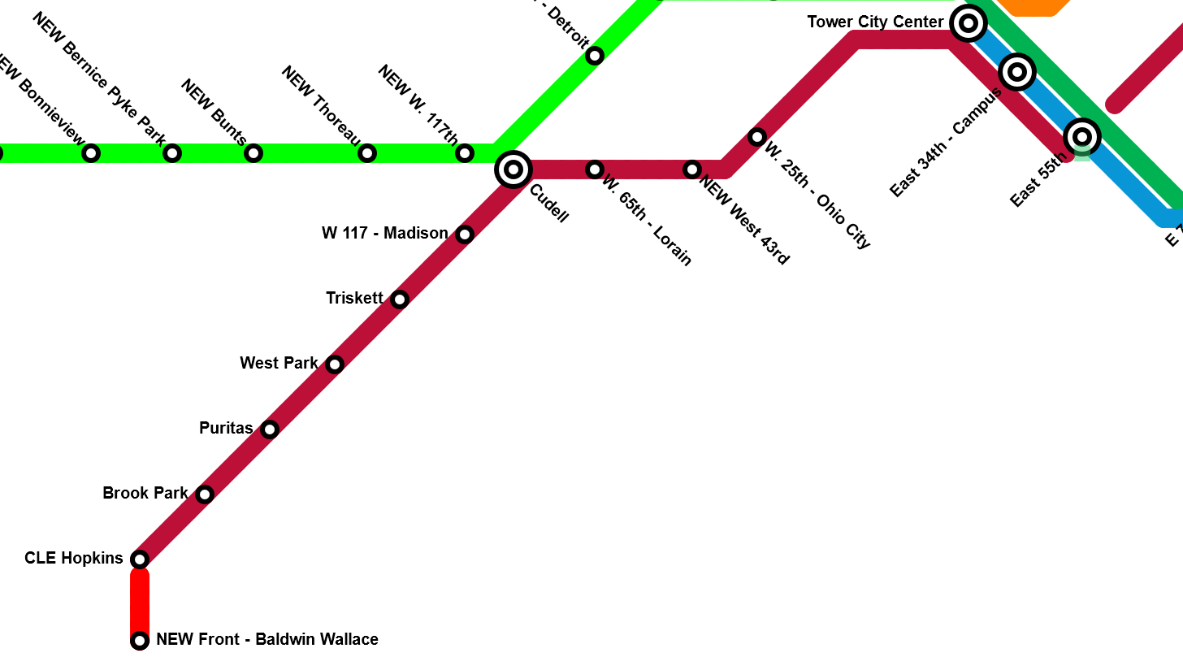

First, expanding Cleveland's flagship rail service and busiest transit line. On the west side, I propose the addition of two new stations, one infill and one extension. After Hopkins, I suggest extending a fresh stretch of line. 2 miles of this would run on current rail, and then it would convert to a streetcar for another half mile down Front Street to connect to central Berea and BW's campus. This touches on a few themes I'll come back to: First, taking advantage of the incoming rolling stock's ability to seamlessly shift from mixed traffic to street level to mixed traffic. Second, bringing educational institutions into the rail network. Additionally, I'm proposing an infill station at W.43rd, because the gap between the W. 25th and W. 65th stations is way too huge.

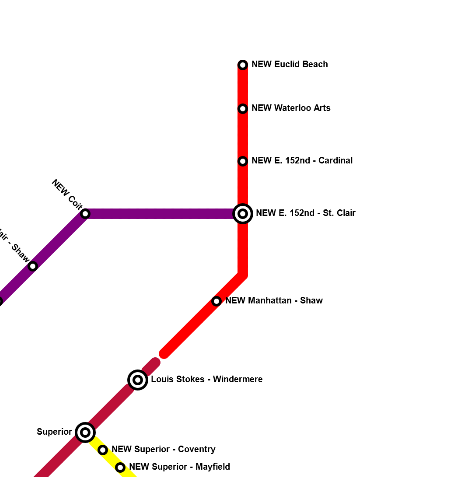

First, expanding Cleveland's flagship rail service and busiest transit line. On the west side, I propose the addition of two new stations, one infill and one extension. After Hopkins, I suggest extending a fresh stretch of line. 2 miles of this would run on current rail, and then it would convert to a streetcar for another half mile down Front Street to connect to central Berea and BW's campus. This touches on a few themes I'll come back to: First, taking advantage of the incoming rolling stock's ability to seamlessly shift from mixed traffic to street level to mixed traffic. Second, bringing educational institutions into the rail network. Additionally, I'm proposing an infill station at W.43rd, because the gap between the W. 25th and W. 65th stations is way too huge. On the east side, I'm suggesting a much more substantial expansion of the Red Line. I suggest that, after Stokes, it continue on that rail spur, with a station at Shaw (close to the high school), then turning up 152nd. Here, it should be new, elevated rail. There are a number of points in this where I suggest the tall but valuable task of fresh elevated rail lines. That would run along 152nd (with stops at St. Clair [Colinwood HS gets service here] and Cardinal) before turning onto Waterloo, hitting the arts district, and then turning back north somewhere between 156th and 164th to run to Euclid Beach Park. Collinwood, especially North Collinwood, is very disconnected from the city in terms of transit. There's also very little transit service to the lake. This seeks to remedy all that.

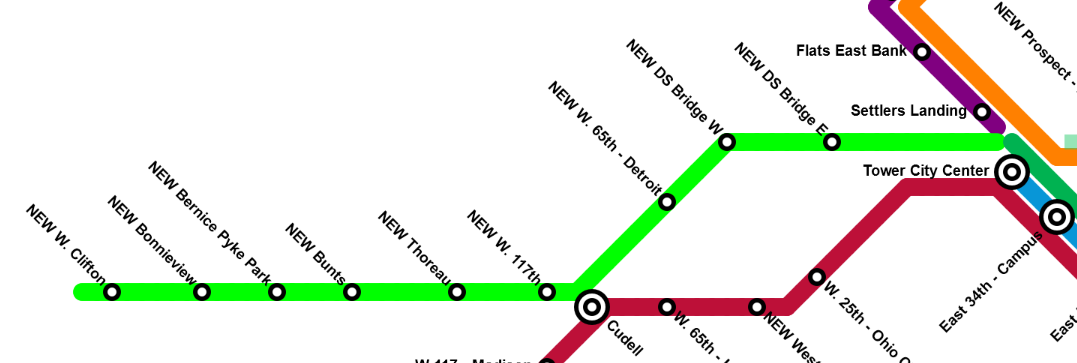

On the east side, I'm suggesting a much more substantial expansion of the Red Line. I suggest that, after Stokes, it continue on that rail spur, with a station at Shaw (close to the high school), then turning up 152nd. Here, it should be new, elevated rail. There are a number of points in this where I suggest the tall but valuable task of fresh elevated rail lines. That would run along 152nd (with stops at St. Clair [Colinwood HS gets service here] and Cardinal) before turning onto Waterloo, hitting the arts district, and then turning back north somewhere between 156th and 164th to run to Euclid Beach Park. Collinwood, especially North Collinwood, is very disconnected from the city in terms of transit. There's also very little transit service to the lake. This seeks to remedy all that. When the Waterfront line was originally built in the 90's, it was supposed to turn back south through downtown and form a loop. I say, let's finish that loop. I suggest going down E. 18th. I know that might seem a little odd, but it neatly hits Playhouse Square and CSU. Then, turn it onto Prospect to hit the Q and the Progressive before taking it down into Tower City. The whole additional stretch here is elevated. I'm also separating this out more cleanly from the Blue/Green Lines and making it definitively its own thing. I see it operating two ways: One, with a regular, dedicated looping service. Second, taking advantage of interoperability to allow any other line hitting TC to add a loop through downtown on some service. For example, if the Red Line were running 6 times an hour, one or two of those would additionally run the whole downtown loop. You could get very, very high frequency on this loop by combining these two options, or even with just the second.

When the Waterfront line was originally built in the 90's, it was supposed to turn back south through downtown and form a loop. I say, let's finish that loop. I suggest going down E. 18th. I know that might seem a little odd, but it neatly hits Playhouse Square and CSU. Then, turn it onto Prospect to hit the Q and the Progressive before taking it down into Tower City. The whole additional stretch here is elevated. I'm also separating this out more cleanly from the Blue/Green Lines and making it definitively its own thing. I see it operating two ways: One, with a regular, dedicated looping service. Second, taking advantage of interoperability to allow any other line hitting TC to add a loop through downtown on some service. For example, if the Red Line were running 6 times an hour, one or two of those would additionally run the whole downtown loop. You could get very, very high frequency on this loop by combining these two options, or even with just the second. It's time to make the Detroit Superior Bridge a subway bridge again. Currently, there are two inaccessible stations at either end of the bridge, and then a tunnel that runs along Detroit to W. 28th. I suggest connecting Tower City's lines underground to the bridge, renovating both bridge terminal stations, and, where the tunnel ends, bringing the line up out of the ground onto new elevated construction. There, it runs above Detroit until connecting into Cudell. Here we hit another theme of my proposal: lines connect far outside of Tower City. This provides a great deal of resiliency to the network as a whole. There's also an alternative option where, instead of going above Detroit, the line turns north immediately after the bridge to hit Whiskey Island and Edgewater, then connecting into Cudell. This would use current rail ROW that could either be taken from NS or built above with elevated rail. Either way, after Cudell, this continues on or over that rail through Lakewood, stopping near the edge with Rocky River. It could feasibly go over the river as well, but I'm only extending to inner ring suburbs here. Lakewood service seems absolutely mandatory to me given its density and linearity.

It's time to make the Detroit Superior Bridge a subway bridge again. Currently, there are two inaccessible stations at either end of the bridge, and then a tunnel that runs along Detroit to W. 28th. I suggest connecting Tower City's lines underground to the bridge, renovating both bridge terminal stations, and, where the tunnel ends, bringing the line up out of the ground onto new elevated construction. There, it runs above Detroit until connecting into Cudell. Here we hit another theme of my proposal: lines connect far outside of Tower City. This provides a great deal of resiliency to the network as a whole. There's also an alternative option where, instead of going above Detroit, the line turns north immediately after the bridge to hit Whiskey Island and Edgewater, then connecting into Cudell. This would use current rail ROW that could either be taken from NS or built above with elevated rail. Either way, after Cudell, this continues on or over that rail through Lakewood, stopping near the edge with Rocky River. It could feasibly go over the river as well, but I'm only extending to inner ring suburbs here. Lakewood service seems absolutely mandatory to me given its density and linearity. This is the first of two proposed completely new lines. It comes off the Waterfront line/loop as a spur. It carries briefly along established rail ROW moving above St. Clair as elevated rail at E. 36th, by Tyler Village. It then runs entirely over St. Clair, stopping every half mile to a mile, until connecting to the Red Line's new St. Clair - W. 152nd station. Again, I'm focusing here on satellite redundancy, hitting underserved areas, and providing good access for students - this line connects to four separate high schools. Taking advantage of interoperability, these trains could continue north onto the Red Line's lakeward extension. This line also serves Asiatown, which is due for rail connection.

This is the first of two proposed completely new lines. It comes off the Waterfront line/loop as a spur. It carries briefly along established rail ROW moving above St. Clair as elevated rail at E. 36th, by Tyler Village. It then runs entirely over St. Clair, stopping every half mile to a mile, until connecting to the Red Line's new St. Clair - W. 152nd station. Again, I'm focusing here on satellite redundancy, hitting underserved areas, and providing good access for students - this line connects to four separate high schools. Taking advantage of interoperability, these trains could continue north onto the Red Line's lakeward extension. This line also serves Asiatown, which is due for rail connection. After Lakewood, Cleveland Heights is the most densely populated city in the state. It's a traditional street car suburb squeezed between RTA's current rail lines. I propose here a mostly street-running streetcar that would link Red, Green, and Blue lines. It hits CH's main cultural institutions, provides further connections for East Cleveland, and brings rail into underconnected Southeast Cleveland. Where possible, I'd be happy to see this as elevated rail, but I think this is one of the few areas where a streetcar is appropriate (even if it's in mixed traffic for most of its time on Lee). This hits CH and SH high schools. It unlocks a huge variety of interoperability options: direct connections to downtown, a variety of looping east side services, massive system redundancy, etc.

After Lakewood, Cleveland Heights is the most densely populated city in the state. It's a traditional street car suburb squeezed between RTA's current rail lines. I propose here a mostly street-running streetcar that would link Red, Green, and Blue lines. It hits CH's main cultural institutions, provides further connections for East Cleveland, and brings rail into underconnected Southeast Cleveland. Where possible, I'd be happy to see this as elevated rail, but I think this is one of the few areas where a streetcar is appropriate (even if it's in mixed traffic for most of its time on Lee). This hits CH and SH high schools. It unlocks a huge variety of interoperability options: direct connections to downtown, a variety of looping east side services, massive system redundancy, etc.