Between December 29 and January 2, 2024, the celebration of the 30th Anniversary of the Beginning of the War Against Oblivion took place in Caracol VIII “Resistance and Rebellion: A New Horizon”, in the Zapatista village of Dolores Hidalgo. The event was organized by thousands of Zapatista support bases, men, women, boys, girls, old men and women who, with faces covered by balaclavas, bandanas and masks, celebrated three decades of resistance to the capitalist system with sports, arts, music, food and popular dance. These lands, recovered after the armed uprising of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) in 1994, are concrete evidence of how Zapatismo in Chiapas has improved the living conditions of the communities based on organization, autonomy and rebellion.

A History

For much of the last century, these lands were owned. In the case of Dolores Hidalgo, an old farmer from Comitán owned thousands of hectares that he used as pastureland. At the top of a small mountain he had a large cabin where he looked over the entire landscape that he had taken from the people with a supposed title deed, as if mother earth had a price. The Tzeltal families of the jungle zone were forced to live in the mountains, where the terrain was unstable and they were denied entry to the supposed “private property” of the so-called Rancho Dolores. There, women, men and children went to work extreme exploitative days. They fed and cared for the employer’s animals, while receiving no pay for their work. The children were not allowed to go to school or play freely, but rather had to fetch water for the pigs and clean the stables. Many of the adult men did not even have money to buy clothes. They covered their bodies with a white cloth tied around their waists and a hole to put their heads through. Meanwhile, the boss even had a small plane to travel to other municipalities in Chiapas. These practices were common in different regions of southeastern Mexico where caciquismo 1 and violence were the norm.

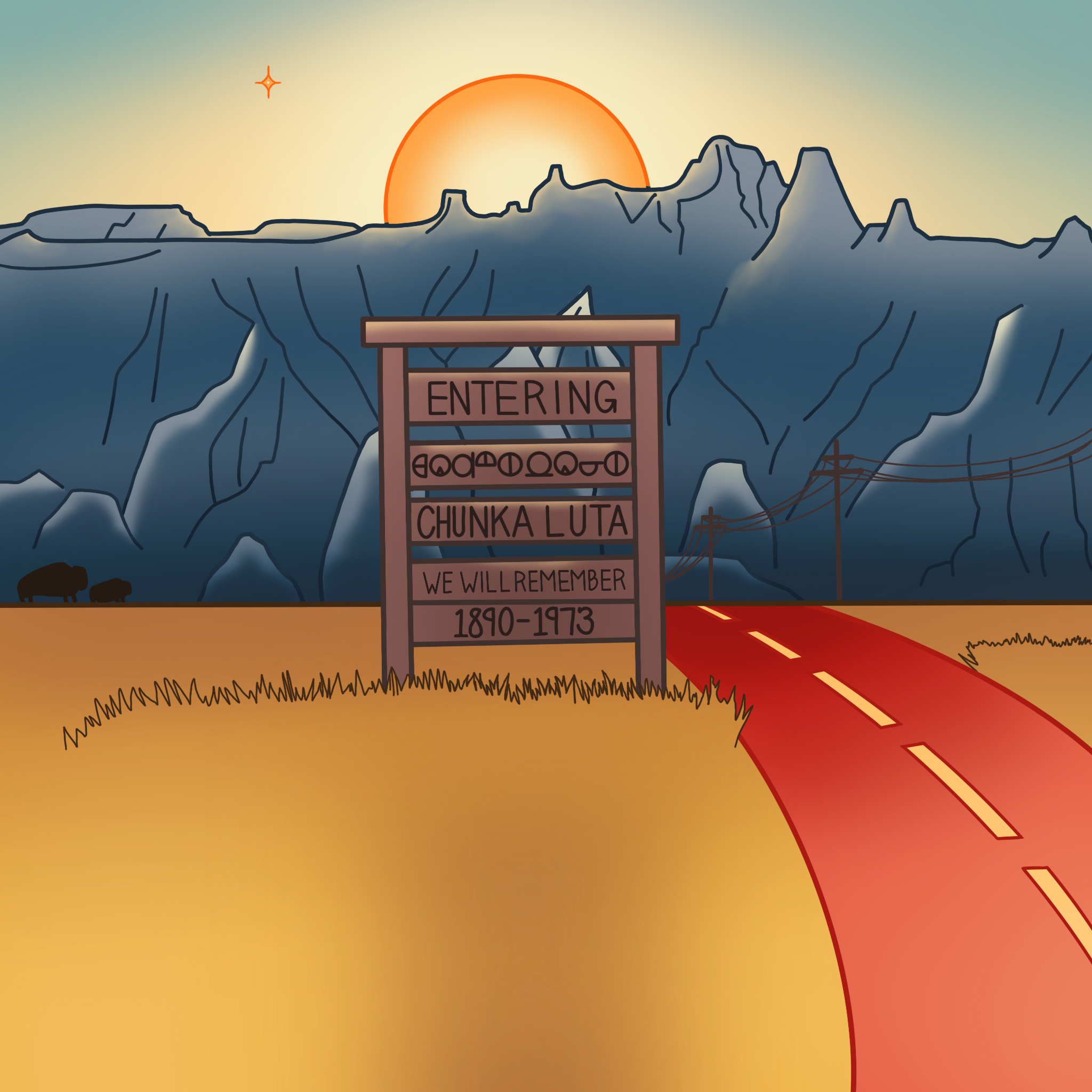

Don Manuel recounted these scenes of the painful past as if they were an excerpt from a B. Traven book. His memory of the oppression and indignities he and his family experienced is present. After the 1994 uprising, the Rancho Dolores landowners practically fled, leaving everything behind. The families recovered these lands, founded villages and began a long process of reconstituting communal life. They organized themselves to rebuild a dignified life, to ensure the “material base” and to pass on a path of resistance to their descendants in order to put an end to the continuous domination. As Don Manuel told his story, his ten-year-old grandson, who his face covered with a red bandana, listened attentively. There is no doubt that today the life of that child is very different from the one lived by Don Manuel who, with pride, looks at the horizon and sentences: “there is no longer a boss, now we have land and we make milpa, we have beans, corn, squash and we have food all year round, because we work collectively.”

read more: https://schoolsforchiapas.org/to-bequeath-life-30-years-since-the-zapatista-uprising/

read more (Spanish): https://regeneracionradio.org/archivos/14516