As federal agencies prepare to deregulate transgenic chestnuts, Indigenous nations are asserting their rights to access and care for them.

This story was co-published with Native News Online

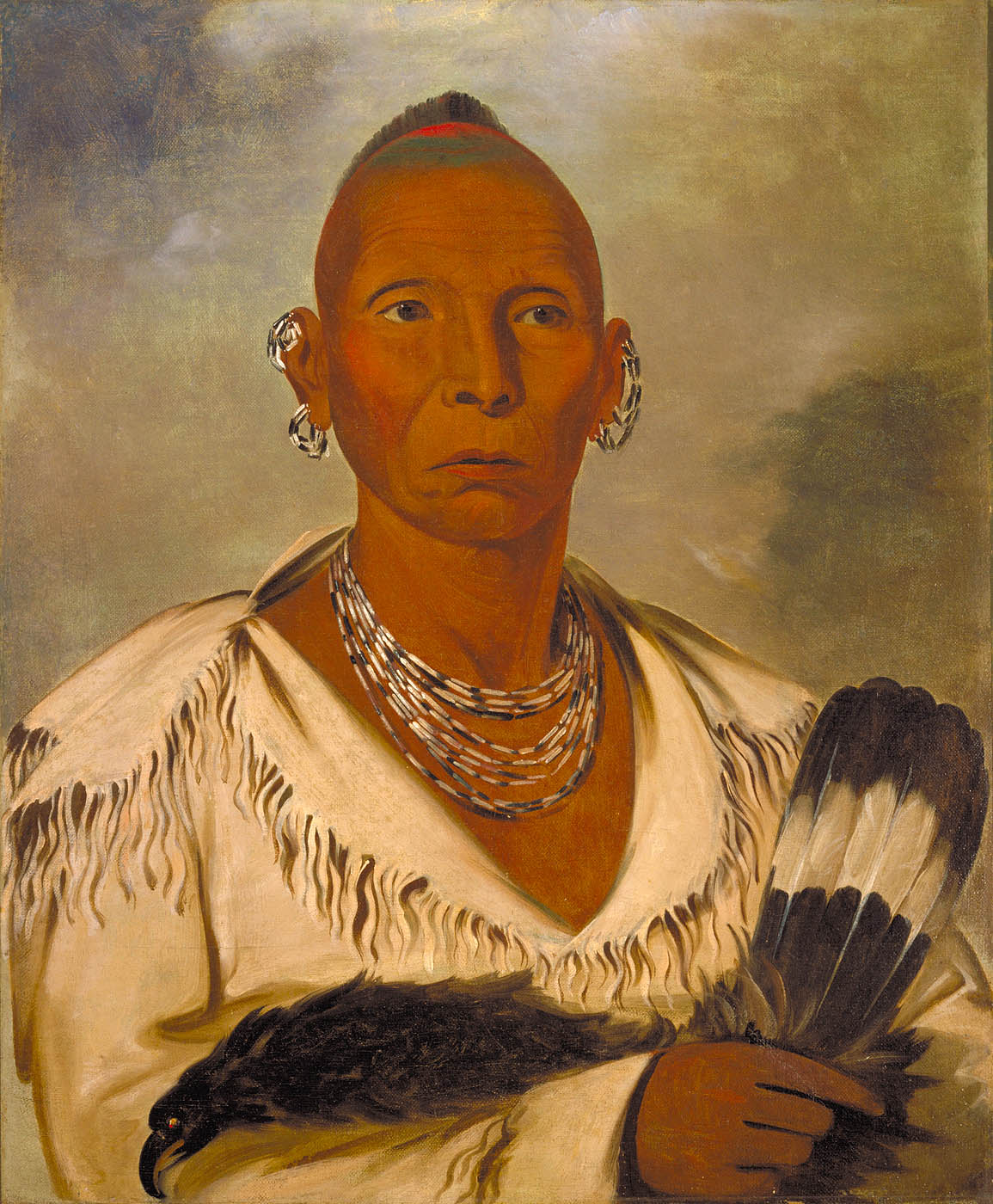

When Neil Patterson Jr. was about 7 or 8 years old, he saw a painting called “Gathering Chestnuts,” by Tonawanda Seneca artist Ernest Smith. Patterson didn’t realize that the painting showed a grove of American chestnuts, a tree that had been all but extinct since his great-grandparents’ time. Instead, what struck Patterson was the family in the foreground: As a man throws a wooden club to knock chestnuts from the branches above, a child shells the nuts and a woman gathers them in a basket. Even the dog seems engrossed in the process, watching with head cocked as the club sails through the air.

Patterson grew up on the Tuscarora Nation Reservation just south of Lake Ontario near Niagara Falls. The painting reminded him of his elders teaching him to harvest black walnuts and hickories.

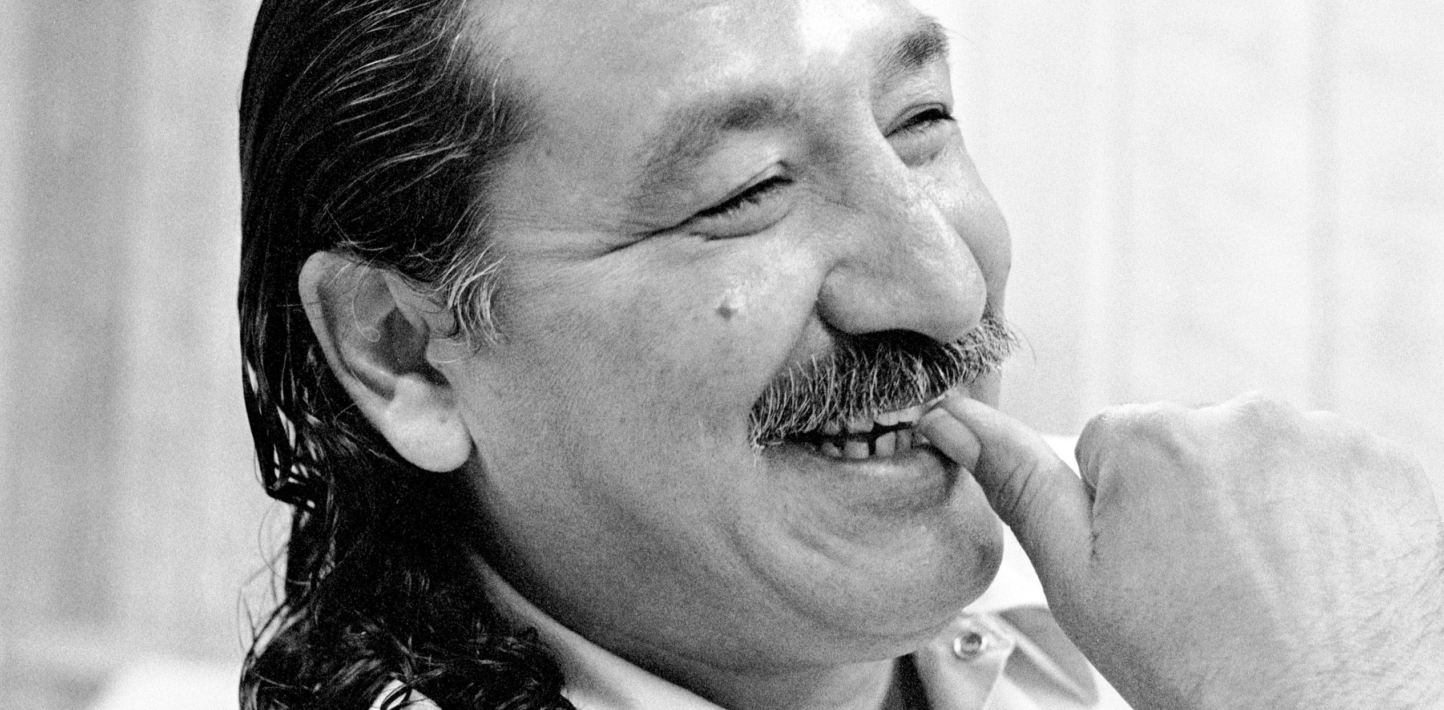

“I think, for me, it wasn’t about the tree, it was about a way of life,” said Patterson, who today is in his 40s, with silver-flecked dark hair and kids of his own. He sounded wistful.

The American chestnut tree, or číhtkęr in Tuscarora, once grew across what is currently the eastern United States, from Mississippi to Georgia, and into southeastern Canada. The beloved and ecologically important species was harvested by Indigenous peoples for millennia and once numbered in the billions, providing food and habitat to countless birds, insects, and mammals of eastern forests, before being wiped out by rampant logging and a deadly fungal blight brought on by European colonization.

Now, a transgenic version of the American chestnut that can withstand the blight is on the cusp of being deregulated by the U.S. government. (Transgenic organisms contain DNA from other species.) When that happens, people will be able to grow the blight-resistant trees without restriction. For years, controversy has swirled around the ethics of using novel biotechnology for species conservation. But Patterson, who previously directed the Tuscarora Environment Program and today is the assistant director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment at the State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse, has a different question: What good is bringing back a species without also restoring its traditional relationships with the Indigenous peoples who helped it flourish?

That deep history is not always clear from conservation narratives about the blight-resistant chestnut. For the past four decades, the driving force behind the chestnut’s restoration has been The American Chestnut Foundation, a nonprofit with more than 5,000 active members in 16 chapters. Before turning to genetic engineering, the foundation tried unsuccessfully to breed a hybrid chestnut that looked and grew like an American chestnut but had genes from species native to Asia that gave it blight resistance. “Our vision is a robust eastern forest restored to its splendor,” reads The American Chestnut Foundation’s homepage, against a background of glowing green chestnut leaflets. “Our mission is to return the iconic American chestnut to its native range.”

But the Foundation website’s history of the tree begins during colonial times, suggesting a romantic notion of a precolonial wilderness that ignores the intensive agroforestry that Indigenous peoples practiced. By engineering vanished species to survive harms brought on by colonization without addressing those harms, people avoid having to make hard decisions about how most of us live on the landscape today.