In Mesoamerican beliefs, a nahual (also called nagual or nawal (from Nahuatl: nahualli 'hidden, concealed, disguise') is a kind of sorcerer or supernatural being who has the ability to take animal form. The term refers both to the person who has this ability and to the animal itself that serves as his alter ego or animal guardian.

The concept is expressed in different native languages, with different meanings and contexts. Most commonly, nahualismo is the practice or ability of some people to become animals, elements of nature or to perform acts of witchcraft.

In Maya, the concept is expressed under the word chulel, which is understood precisely as "spirit"; the word derives from the root chul, which means "divine".

According to some traditions, it is said that each person, at the moment of birth, already has the spirit of an animal, which is in charge of protecting and guiding him or her. These spirits usually manifest themselves only as an image that advises in dreams or with a certain affinity to the animal that took the person as its protégé. A woman whose nahual was a mockingbird will have a privileged voice for singing, but not all have such a light contact: it is believed that the sorcerers and shamans of central Mesoamerica can create a very close bond with their nahuals, which gives them a series of advantages that they know how to take advantage of, the vision of the sparrow hawk, the wolf's wolfhound or the ocelot's ear affirm.

Beliefs

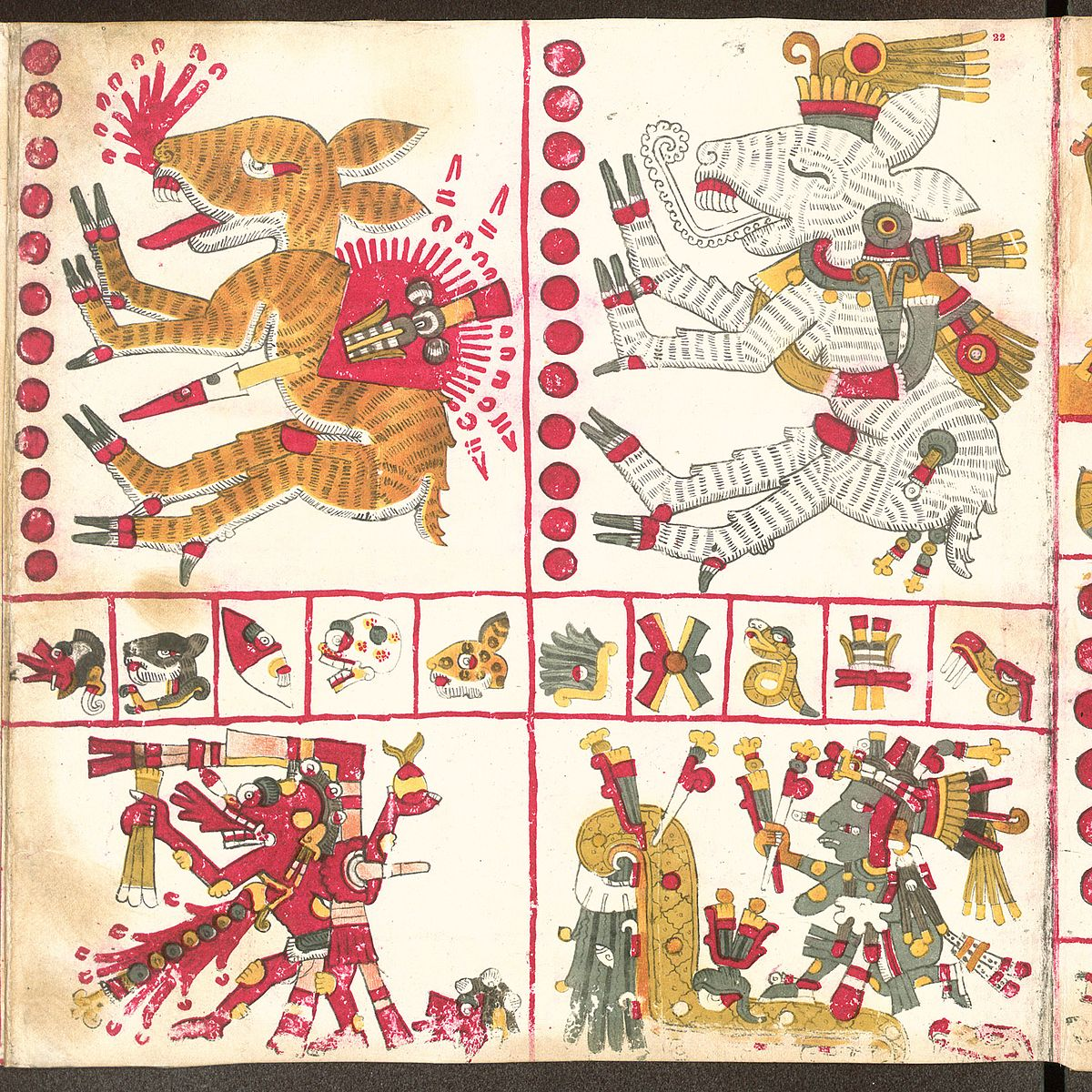

Naguals use their powers for good or evil according to their personality. The general concept of nagualism is pan-Mesoamerican. Nagualism is linked with pre-Columbian shamanistic practices through Pre-classic Olmec and Toltec depictions that are interpreted as human beings transforming themselves into animals. The system is linked with the Mesoamerican calendrical system, used for divination rituals. Birth dates often determine if a person can become a nagual. Mesoamerican belief in tonalism, wherein every person has an animal counterpart to which their life force is linked, is drawn upon by nagualism

The Western study of nagualism was initiated by archaeologist, linguist, and ethnologist Daniel Garrison Brinton who published Nagualism: A Study in Native-American Folklore and History, which chronicled historical interpretations of the word and those who practiced nagualism in Mexico in 1894. He identified various beliefs associated with nagualism in modern Mexican communities such as the Mixe, the Nahua, the Zapotec and the Mixtec.

Description

In Mexico, the name nahuales has been given to sorcerers who can change their shape. However, it is believed that contact with their nahuales is also common among shamans who seek to benefit their community, although they do not use the ability to transform; for them, the nahual is a form of introspection that allows those who practice it to have close contact with the spiritual world, thanks to which they easily find solutions to many of the problems that afflict those who seek their advice.

Since pre-Hispanic times, the gods of the Mayan, Toltec and Mexica cultures, among others, have been attributed the power to take the form of an animal (nahual) to interact with humans. Each deity used to take one or two forms; for example, Tezcatlipoca's nahual was the jaguar, although he indistinctly used the form of a coyote, and Huitzilopochtli's was a hummingbird. According to Michoacán traditions, the nahuales sometimes transform into elements of nature, and are sometimes confused with the graniceros, although there are similar references in various cultures that lend themselves to confusion, and it is likely an amalgam of other cultures where the change of form is to elements of nature and not to animals.

Megathreads and spaces to hang out:

- ❤️ Come listen to music and Watch movies with your fellow Hexbears nerd, in Cy.tube

- 💖 Come talk in the New Weekly Queer thread

- 💛 Read and talk about a current topics in the News Megathread

- 💚 Come and talk in the Daily Bloomer Thread

- ⭐️ September Movie Nominations ⭐️

reminders:

- 💚 You nerds can join specific comms to see posts about all sorts of topics

- 💙 Hexbear’s algorithm prioritizes comments over upbears

- 💜 Sorting by new you nerd

- 🌈 If you ever want to make your own megathread, you can reserve a spot here nerd

- 🐶 Join the unofficial Hexbear-adjacent Mastodon instance toots.matapacos.dog

Links To Resources (Aid and Theory):

Aid:

Theory: